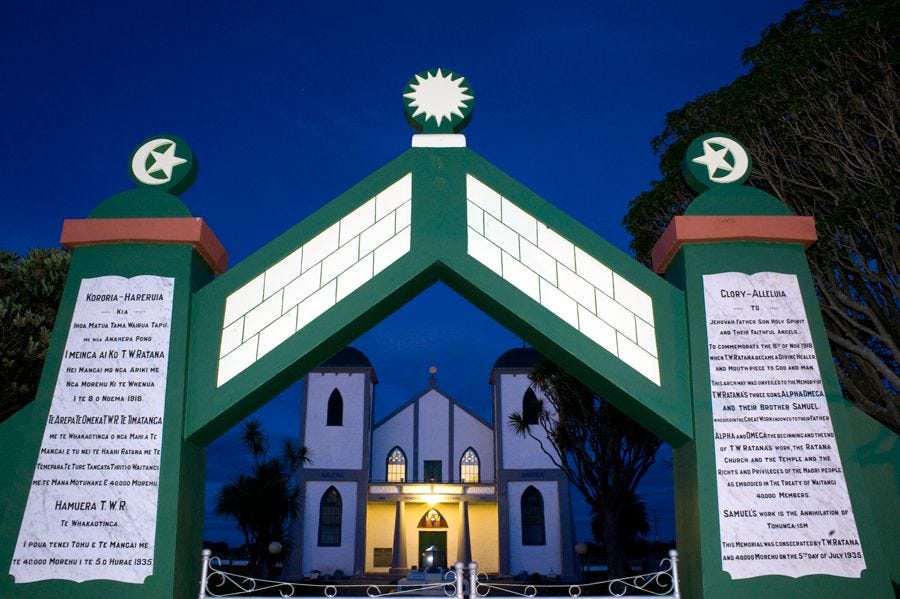

Every January, Aotearoa’s political year begins with a familiar journey up the coast from Pōneke to Rātana Pā. Politicians arrive, shake hands and speak carefully beneath the weight of history. Attendance has never guaranteed harmony, but presence itself has long been the point. To turn up was to acknowledge continuity of faith, of Te Tiriti relationships, of obligations that outlast any single government.

In 2026, the country watched a different journey instead.

As thousands gathered at Rātana, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon travelled east — to flooded roads, damaged homes and communities once again beginning the slow work of recovery along the East Coast and Northland. The reason was neither trivial nor symbolic. Severe weather had displaced families and severed infrastructure. Prime ministers go where the damage is.

And yet politics is shaped not only by reasons, but by what those reasons displace.

Rātana has endured precisely because it sits outside the daily churn of government. It is one of the few remaining political rituals in Aotearoa where urgency is meant to pause, where the state acknowledges that some relationships cannot be managed on a rolling crisis basis. This year, that pause did not occur. Disaster response took precedence. Necessity won.

That choice was defensible; it was not neutral.

What felt different in 2026

The Prime Minister’s absence did not derail the proceedings. Ministers and politicians attended. Protocol was observed. Rātana endured, as it always has.

What changed was the temperature. The tone was cooler, flatter, more pragmatic. Expectations were lower. Not because grievances had softened, but because confidence in symbolic moments delivering political movement has dwindled. Māori leaders spoke less as petitioners and more as institutions accustomed to resilience, signalling willingness to work with whoever was prepared to engage, without illusion about what attendance along could achieve.

This was not rupture, but a reset.

Historically, Rātana has functioned as a point of alignment (not of agreement, but of recognition), between Māori political authority and the Crown. That alignment relied on an assumption of return: that even when progress stalled or has been threatened, the relationship itself remained central enough to be revisited, year after year.

In 2026, the relationship was acknowledged but felt like it no longer organised the political moment.

From continuity to permanent response

This shift cannot be understood through symbolism alone. It reflects a deeper change in how the state is governing.

Flooding along the East Coast was not an exception. It was part of a cycle that has become grimly familiar. Climate-driven disasters are no longer interruptions to governance; they are standing conditions within it. Emergency response, infrastructure repair and fiscal triage now permanently compete for political attention.

In that environment, politics reorganises itself around immediacy. Presence follows damage. Decisions are made for visibility and speed. Rituals persist, but only insofar as they do not compete with crisis.

This is what governing in permanent response mode looks like. It does not reject continuity outright — it simply cannot prioritise it.

Political relationships designed for patience, repetition and long memory strain under these conditions. They survive, but thinly. Maintained, but conditionally. The risk is not overt disrespect, but quiet demotion.

Rātana, kaitiakitanga and consequence

What is often missed in standard political analysis of Rātana is that its concern was never limited to representation alone. From its earliest teachings, the Rātana movement treated land, water and people as inseparable. Not symbolically, but materially. Care for the environment was not an adjunct to justice; it was its precondition. Kaitiakitanga was assumed, not argued for. That matters now.

In 2026, the Prime Minister’s absence from Rātana was caused by flooding. Not metaphorical, not future-dated, but present and destructive. People dead, homes inundated, roads cut. Communities rebuilding, again. The state did not turn away from Rātana out of indifference, but because it was responding to environmental failure in real time.

There is a bitter symmetry here. A movement grounded in stewardship, restraint and long memory now finds its annual political movement displaced by the consequences of decades in which those principles were subordinated. The country is no longer debating kaitiakitanga in theory. It is living with its absence — measured in muddy waters and landslips, subsequent infrastructure and loss of loved ones, and recurring emergency.

The costs of governing by response are not evenly distributed. For Māori, whose political relationships are grounded in continuity, land and stewardship rather than mobility and abstraction, postponement is not neutral. When continuity gives way to crisis management, it is Māori communities who are more likely to absorb the delay — environmentally, economically and institutionally.

This is not environmental responsibility arriving late; it is environmental responsibility enforced by disaster.

Landing the question

Rātana was built for a political tempo that assumed time, return and repair. Its power lay in repetition: each year reaffirming a relationship that could be strained, deferred, even contested — but not displaced. Continuity was the point. Presence substituted, briefly, for resolution.

Permanent response governance breaks that logic. So, the question sharpens:

What happens to political relationships designed for continuity when the state itself now governs in permanent response mode?

In 2026, Rātana still gathered. It still spoke. It still endured. But history waited while the state responded elsewhere. That choice was reasonable. It was also revealing.

If continuity can now be postponed indefinitely by necessity, then legitimacy can no longer rely on inherited forms alone. It will have to be carried by structures capable of surviving crisis — not rituals that must step aside for it.

That is not a failure of Rātana. It is a signal about the country we are becoming.