When Progress Outpaces Democracy

Eco-populism, moral urgency and the risk that it poses to Aotearoa's left

As Dr Bryce Edwards argues in his most recent briefing for The Democracy Project, the Greens in Aotearoa are not struggling because their values have drifted from public sentiment. On climate breakdown, inequality, housing precarity and global justice, they remain broadly aligned with where much of the electorate says it wants to go. And yet, over the past year, polling has softened rather than strengthened. Influence has thinned rather than consolidated. Moral clarity has not translated into political leverage.

This is not an ideological failure. It is a failure of traction.

And that failure matters because, at precisely the same moment the Greens have stalled domestically, progressive movements elsewhere have demonstrated how quickly traction can be manufactured when restraint is set aside.

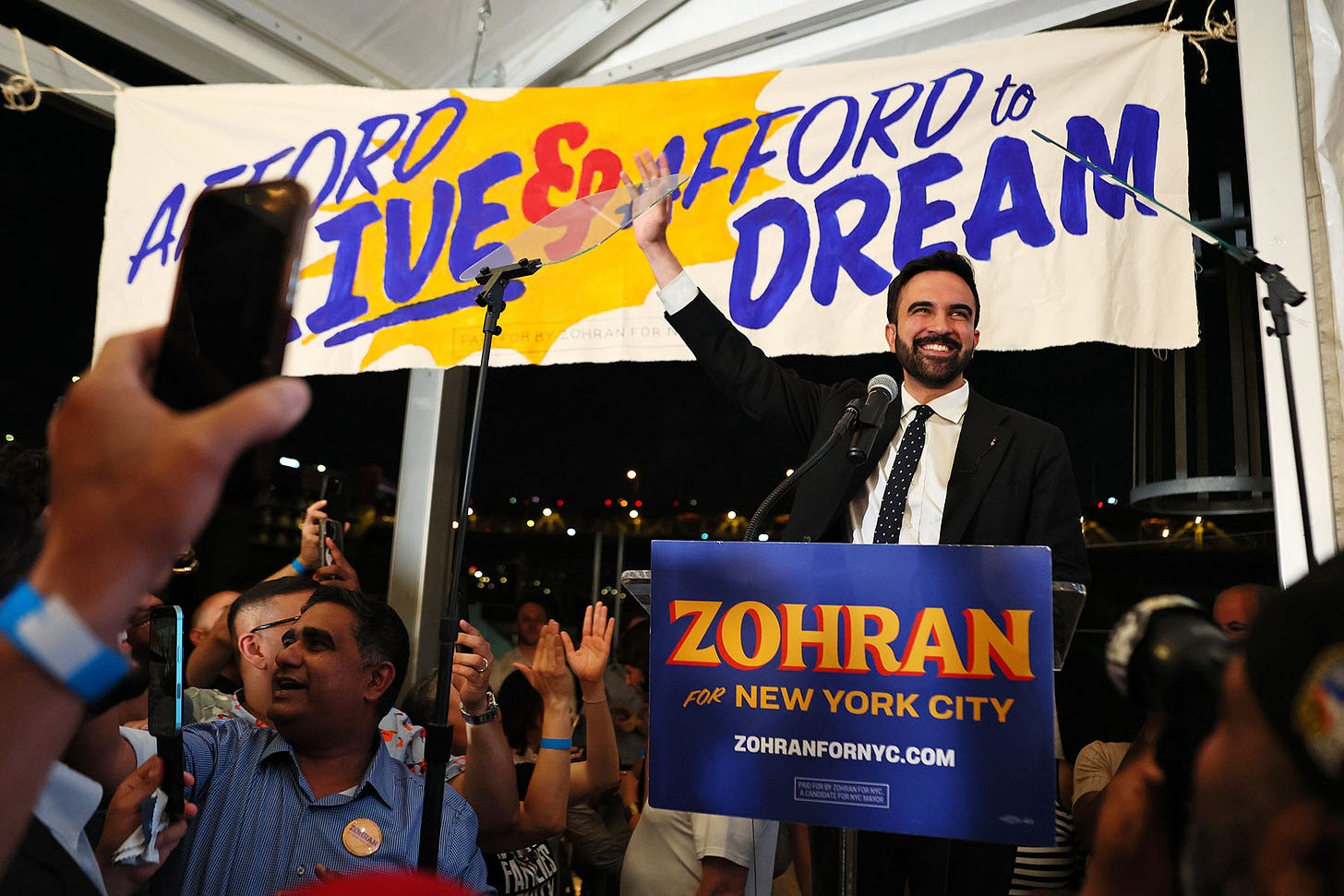

The lesson from New York: speed as legitimacy

The clearest contemporary case study is New York.

Zohran Mamdani has shown finally how progressive politics can move with striking velocity when moral urgency, identity and disciplined antagonism are fused into a single political strategy. Campaigns that once took years of persuasion have been compressed into months. Ideas that once lingered at the margins of debates have been hauled rapidly into the centre.

This is not governance yet. It is mobilisation. But mobilisation at this scale produces its own legitimacy, particularly in political systems already strained by inequality, crisis and institutional delay (all of which feel very pressing in Aotearoa at the beginning of 2026).

Mamdani’s achievement is not ideological novelty. It is operational clarity. He does not argue institutions are wrong. He argues that they are late. And in a political environment saturated with urgency, lateness itself becomes a moral failing.

Speed, in this framing, is no longer merely tactical. It becomes ethical.

The UK signal: hardening the logic

Across the Atlantic, the UK illustrates how this strategy evolves once momentum is established.

Figures such as Zack Polanski matter less as proof of electoral success than as indicators of rhetorical hardening. Where Mamdani demonstrates how power can be accumulated, Polanski’s interventions point to how it is defended: by narrowing the space in which disagreement is treated as legitimate.

Here, we see politicking used as a structural tool. Moderation is reframed as obstruction. Proceduralism is recast not as a democratic safeguard but as evidence of bad faith. Institutional friction ceases to be an expected feature of democracy and becomes proof that system itself is compromised.

This logic travels easily. It does not require identical conditions — only the same moral framing.

Why this tempts the New Zealand left

For left-leaning parties in Aotearoa (particularly the Greens and increasingly Labour), the appeal of these tactics is obvious.

Politics in Aotearoa is slow by design. Institutions privilege consensus. Change arrives incrementally, often after the moment of urgency has passed. In that context, eco-populist acceleration does not feel radical. It feels efficient.

Progressive populism also carries a powerful moral insulation. Its values are widely shared. Its objectives are defensible. Its antagonists are structural rather than personal. This creates a dangerous assumption: that good intentions provide protection against misuse.

History suggests they do not.

South Africa as a boundary case study

In a period of unprecedented global volatility and renewed waves of populism across advanced democracies, it is worth keeping even extreme historical cases in mind. Not because their outcome is likely to recur, but because they make visible the underlying mechanics by which democratic systems can be hollowed out when moral urgency begins to substitute for institutional constraint.

Post-liberation South Africa offers a particularly instructive case.

The African National Congress entered government with extraordinary moral legitimacy, earned through decades of struggle against apartheid. Its democratic commitments were sincere. Its early achievements were real. Few political movements have begun with a stronger ethical mandate.

Over time, however, liberation legitimacy began to substitute for institutional accountability. Political opposition was increasingly framed not as disagreement, but as resistance to justice itself. Criticism was recast as obstruction. Electoral dominance was interpreted not merely as consent, but as moral endorsement.

The erosion that followed was not imposed by force, nor announced in constitutional rupture. It was normalised. Democratic forms remained intact, but pluralism1 weakened as moral authority crowded out contestation.

The relevance of this example lies not in its outcomes, but in its internal logic: when justice is framed as urgent and earned, disagreement begins to look illegitimate — and institutions designed to slow power down are recast as obstacles rather than safeguards.

A note on what this argument is not

Two objections surface in my mind at this point as I read the above. I believe clarifying them sharpens my case.

First, this is not an argument against urgency. As my previous articles detail in-depth, climate breakdown, inequality and institutional failure are real and accelerating. Delay has compounding consequences. Moral intensity in politics is often a rational response to lived harm.

What is at issue here is not urgency itself, but how urgency is converted into authority. Democratic systems are not weakened by passion. They are weakened when passion is allowed to substitute for institutional constraint, and when disagreement is recast as obstruction rather than participation.

Second, this is not any form of accusation of bad faith against Mamdani, Polanski, the Greens or any progressive movement. As a young Kiwi, the progressive movement excites me and feels like genuine progress. The risk I identify does not require cynical leadership or authoritarian intent. It emerges precisely when movements believe their values provide insulation against misuse.

History suggests that democracy is rarely hollowed out by those who reject it outright. It is more often weakened by those who believe they cannot afford to wait for it.

The manipulation risk populism creates

This is the danger progressive populism consistently underestimates.

Populism does not persuade citizens to abandon democracy. It persuades them that key aspects of democracy is slowing justice down. Once that belief takes hold, it can be activated by anyone — not only by those who began with principled aims.

In a high-trust system like Aotearoa’s, this risk is magnified. Our institutions rely less on enforcement than on consent. They function because friction is broadly accepted as legitimate. A politics that treats friction as moral failure does not collide loudly with this system. It erodes it silently.

In New Zealand, populism is more likely to seep than it is to shout.

The question the Greens cannot avoid

The Greens’ polling weakness is not evidence that restraint should be abandoned. But neither is it proof that restraint will be rewarded indefinitely. The political environment is shifting. Velocity is becoming a form of credibility. Movements that move fastest increasingly shape the agenda — not because they are most correct, but because they are most decisive.

The lesson from New York is not urgency is wrong. It is that urgency, once weaponised, does not come with built-in limits. Democratic safeguards do not survive acceleration by default; they must be named, reinforced and defended deliberately. Without explicit guardrails, populist acceleration is not reform. It is leverage without a limiter.

And once speed becomes the moral benchmark of politics, restraint has no natural defence.

The question facing the New Zealand left is not whether it can move faster. It is whether it can do so without teaching the system that speed outranks pluralism — because once that lesson is learned, it will not belong to the left alone.

By then, it will be too late to pretend the risk was unforeseeable.

A political system where there is power-sharing among a number of political parties, like MMP in Aotearoa

Oh dear. The Greens’ polling isn’t a democratic risk. People can see a lack of competence. The wish list may be costed, but it isn’t funded. The morality isn’t funded either. They talk about long-term benefits but skip the short-term costs. And we’re a small economy — we can’t pretend we’re a big one.